End of Support for Microsoft Products: What You Need to Know

Stay informed about the end of support for Microsoft Office 2016 & 2019, Exchange Server 2016 & 2019, and Windows 10.

With the arrival of any transformative technology, those wishing to exploit it ethically or otherwise always arrive with it. The digital communication era has been no different. The nuisance of email spoofing and forgery threatens digital security on every level of society, from personal email to corporate communications.

Email spoofing is the use of forged sender addresses to fool recipients into opening the message, which can result in the delivery of malicious code, misinformation and other seriously bad outcomes. Without an authentication mechanism for core email protocols, this type of spam can become the worst kind of headache. Companies around the world suffer significant losses each year because of such email attacks, and forged email attacks are among the most widespread.

This story happens somewhere everyday.

One company, which we’ll call Alice, Inc. (“Alice”), was carrying on correspondence with another company, Bob, LLC (“Bob”). Alice wanted to purchase high-value equipment from Bob. One day in the middle of negotiations, it became necessary for Alice to change its bank account details. Additionally, along with their own troubles regarding the account details change, Alice received an e-mail detailing changes to Bob’s account as well.

“Misfortunes never come alone,” thought the accounts manager at Alice company, who opened the email.

Fortunately, Bob’s account information had not been changed. Unfortunately, the email wasn’t from Bob at all, but from Mallory, a swindler who successfully forged Bob’s address. It was almost impossible to identify the spoof.

It turns out that another employee from Alice had received an earlier email with Mallory’s embedded code. It was a sales invoice in *.exe archive form. Antivirus failed to detect the malware in the message at the time it was received. After a few days, antivirus signatures were updated and the malware was removed, but the sender’s email address had already been forged, and money had been transferred to Mallory’s account.

The address substitution was performed in a simple way. Here’s how.

The correct sender’s address: accountant@alice.email

The forged sender’s address: accountant@alice.email <accountant@bob.email>

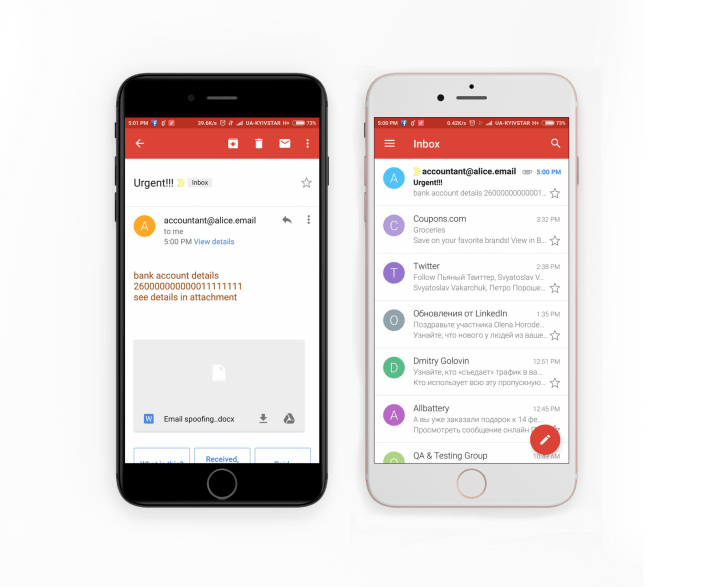

The swindler’s email account included the name accountant@alice.email. The Alice employee who was keeping the correspondence was doing that, partly using the mobile device, and the email client of device showed just the sender’s (Mallory’s) name.

This is why the incoming message was depicted as being from accountant@alice.email. It looked very similar to the original.

The deception remained unrevealed until the moment when Bob called Alice and asked where the money was. Fortunately, due to changing account identification from both sides, the bank prevented the money being transferred to Mallory’s account. It was transferred instead to the bank’s transit account until confirmation. Alice was able to get the money back.

This story has a happy ending. It isn’t always so.

Spoofers utilize different methods in their attacks. Often a malefactor sends the forged message that appears to be on behalf of a company executive. It might contain a demand for an urgent reply or other response from an employee or group. It may demand sending some type of restricted information that may well result in sensitive data leakage. It might also order an employee to make a bank transmission of a substantial sum of money. Hopefully, a company has non-digital business processes in place that would prevent this type of forgery from being successful, but it is not unheard of for an employee to feel pressure to comply with such an urgent request. Furthermore, an attack may be preceded by reconnaissance with use of social engineering that is aimed at finding the group of employees who will receive the forged letter. This kind of approach is also beneficial to the attack’s success. Additionally, employing robust email search tools can help authenticate sender details, providing an extra layer of protection against spoofing and forgery attempts.

To sort out how email forging works, it will be useful to recall the structure of an electronic message sent through Simple Mail Transfer Protocol, or SMTP.

SMTP is an Internet standard for electronic mail (email) transmission. First defined by RFC 821 in 1982, it was last updated in 2008 with Extended SMTP additions by RFC 5321, which is the protocol in widespread use today.

It consists of envelope, headers and message body. Information about the sender is contained in the envelope. This information is formed by SMTP command “MAIL FROM” and works on a message sending process while it transmits Mail Transfer Agent. However, the information about the sender is also contained in some message headers, such as “From:”, “Return-Path:”, probably “Reply-To:”.

Headers are significant for email clients, e.g., Mozilla Thunderbird. Headers are used to fill appropriate fields.

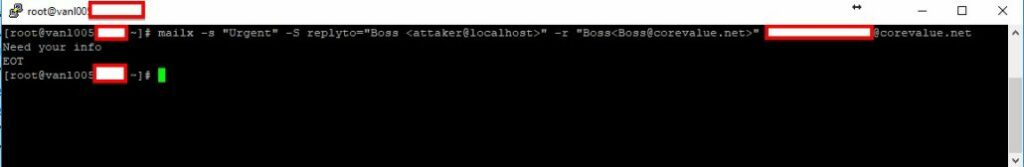

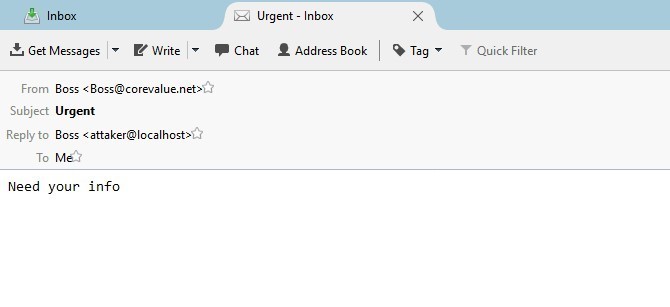

Consider the following example of an SMTP command to send a message with the forged headers “From:” and “Reply-To:”. We are connecting to the Mail Server by using SSH:

mailx -s “Urgent” -S replyto=”Boss <attaker@localhost>” -r “Boss<Boss@test.corevalue.net>” mymail@test.corevalue.net

The message is sent from the genuine address root <root@vanl005.online.com>, but in the header “From:” we insert the name and address of the company’s CEO. At the same time, we insert address attaker@localhost in header “Reply-To”, an address to which an unmindful employee will send the restricted information. Finally, when the letter is opened in Thunderbird, it will look like this:

After clicking “Reply”, the recipient’s address will be autosuggested.

As you can see in the example above, forged messages can be sent with little difficulty when mail transfer agent is not secured.

The situation gets worse for mobile devices users. The concept of mobility implies that we act rapidly, ASAP, doing it now! Moreover, we operate on a small screen, often not paying much attention to details. In the story above, it was the “mobility” factor that took its toll.

There is no single answer as to how to deal with forged messages. Protection from this kind of attack requires the use of crosscutting and aggregated approaches. Here are a few.

Methods 1-3 are first-level filters. They deal with bulk mailing (SPAM) and malicious email, which includes messages with fraudulent sender. In this case, malefactors use an all-out attack effect, neither performing preliminary reconnaissance nor trying to match content to a particular recipient. These may be messages sent in bulk on behalf of bank officials with requests to report restricted information.

Methods 4-6 deal with situations where senders’ names in message headers are placed precisely to a sign.

Method 7 fits instances similar to the above story, when the message header was modified to look like the genuine one. However, the header in the forged message differs from the header of genuine sender, which allows the malefactor to circumvent checking by methods 4-6.

Let’s consider the mentioned above methods more closely.

1. Filtering based on a sending server’s reputation. If a corporate mail security system offers a qualitative base of senders’ reputations, it becomes possible to filter out a significant amount of spam and malicious messaging at the point of TCP-session establishment, without the need to look into either body or envelope of the letter. This approach appreciably saves system resources. The moment sender tries to set the TCP-session on port 25, the security system defines the reputation for sender’s IP-address and makes the decision.

2. Filtering based on checking DNS records of sending server. The mail sender must be registered in DNS correctly. The PTR record, as well as A record, must also be correct. Sender must be correctly introduced in SMTP command HELO. While creating a bulk mailing, malefactors constantly change IP-addresses of sending servers. They do it every day, or even more frequently. It is hard to register required DNS records, so many spam disseminators neglect such requirements. This helps to filter them by DNS attributes.

3. Filtering based on checking DNS records of sending server. Information in “MAIL FROM” is also subject to inspection by DNS. The letter may be rejected if:

1. There is no information about the sending domain in the envelope.

2. Domain name is not permitted in DNS.

3. Domain name does not exist in DNS.

4. Filtering by checking SPF records. Sender Policy Framework (SPF) is a system checking an email sender. Checking by the DNS records of the sending server means that the required PTR and A records in DNS exist for sender’s IP-address. However, these procedures never define whether the sending server is allowed to send messages from the specified domain. It is worth mentioning that A records of mail servers often contain company’s domain name, for example, smtp01.mycompany.com. In this case, when the server is used for mail reception, the same A record will be included in the MX record. It is likely that if the message from mycompany.com was sent from server smtp01.mycompany.com, then the message is genuine. Otherwise, if the message was sent from smtp01.anythingelse.com, then it is forged.

In the meantime, companies often email using auxiliary servers MTA, e.g., their providers’ servers, etc., instead of directly from their own mail servers. This can lead situations where messages from domain mycompany.com are sent from servers smtp01.provider.com, etc. Canonical names of servers do not belong to the company’s domain mycompany.com.

How can the recipient know whether sending servers are legitimate or not? SPF solves this task. The task can be solved with the help of DNS by publishing a special TXT record. This TXT record includes IP-addresses, subnets or A records of servers, which could send mail. Those servers are not regarded as legitimate senders. Using SPF, sender can resort to DNS and define whether or not he could trust sender’s server, or whether the sending server is trying to simulate somebody else.

At this time, not every company forms SPF records.

5. Filtering by DKIM. Domain Keys Identified Mail (DKIM) is an email authentication method. Turning back to the example when company mycompany.com mails correspondence out through provider’s MTA smtp01.mycompany.com, MTA works with SPF records. This is why mail from mycompany.com passes checking procedures successfully. However, if MTA data turns out to be compromised, is the malefactor also able to send forged messages via these servers? How do you authenticate sender in this case? The answer is email authentication.

Authentication uses asymmetric cryptography and hashing functions. Private key is known only to the sending server. Public key is published with the help of DNS in a special TXT record. The sending server forms the print of message headers using hashing functions, and signs it using private key. The signed print is added to the message header DKIM-Signature. Now, by using the public key, recipient can get the decoded print and compare it with the print of received message fields because the hashing function is known. If prints match, signed headers were not changed while being sent, and the sender that formed header DKIM-Signature is legitimate.

6. Filtering by DMARC. Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting and Conformance (DMARC) is a system that describes how to use check results made by SPF and DKIM. DMARC policies are published by DNS in TXT record. They define what specifically should be done to the message on the recipient’s side, and depends on SPF and DKIM check results. DMARC also provides the sender with reverse communication with the recipient. Sender may get reports about all the emails with the sender’s domain. The information will include IP-addresses of sending servers, quantity of messages, in accordance with DMARC policies, and SPF and DKIM check results.

7. Creating granular filtering in manual way. Unfortunately, not every company uses SPF, DKIM, or DMARC, while sending email. On the other hand, sometimes SPF, DKIM and DMARC checks may run successfully, but messages may be forged anyway. For those cases, the solution is filter tuning. Different system capabilities for filter rules are variable. Filters tuning depends on different ways the attack may be arranged, as well as on peculiarities of mail system organization in the company. For example, some companies may receive messages with the same company domain-sender. Setting stronger spam filters may help, assuming this is allowed by your mail provider. If you can use services like Gmail’s Priority Inbox or Apple’s VIP, you essentially let the mail server figure out the important people for you. If an important person is spoofed, you will still receive it, however.

8. Never click unfamiliar links or download unfamiliar attachments. This may seem like a no-brainer, but all it takes is one employee in a company seeing a message from their boss or someone else in the company to open an attachment or click a funny link to expose the entire corporate network. Many of us think we are above being tricked that way, but it happens all the time. The following are general best practices rules to which everyone in your company should adhere:

Email attacks with sender’s falsification are widespread. Successful ones may lead to miserable consequences affecting both individual employees and the whole company. Material losses and restricted information leakage are possible. Among the methods to protect against attacks, 7 and 8 can be regarded as the easiest and most effective.

We hope the article will make you aware of how simple and dangerous a forged message can be, as well as ways to defend yourself and your company.

Ready to innovate your business?

We are! Let’s kick-off our journey to success!