Automotive industry trends 2025: Shifting gears toward innovation

Delve into the automotive industry trends of 2025 and beyond, where consumer preferences and autonomous vehicles converge to redefine mobility.

HTTP was originally created to transmit HyperText but quickly became the most common networking (level 7) backbone of all internet applications, both in the front and in the backend as well. It’s the most commonly used application level protocol for any business or consumer application.

That’s why it is important that this critical foundation, for the entire internet and business application ecosystem, is going through significant changes.

It was a classical HTTP, on top of a TCP connection; slow but reliable. A client sends a text request, like GET, to receive a web page and based on the page contents it sends another HTTP request to get images, JS scripts, and style sheets.

It was simple, connectionless, and stateless, but slow with high latency.

It was the default HTTP protocol version for most of the internet for years, and it is still in use today. Probably the most important improvement was to keep alive extensions in the protocol, which enabled the reuse of existing TCP connections to send more requests and receive more content. The cost of closing and opening TCP could be avoided.

However, new tricks had to be developed as a response to the limitations of HTTP/1.1. Especially the limitation of concurrent connections between the browser and the HTTP server (2-8 usually), like multiple domains for images, scripts, style sheets and web page content, in order to overcome the limitations. Still there was a limit of one request at a time so the hunger for more connections was even greater.

Additionally HTTPS became the default; an encrypted channel for all web apps and APIs, so the need for better support in this situation was required.

→ Web apps – all the things you don’t have to do on your own.

The need for faster technology was apparent, however, Google wasn’t looking for a new standard to be established and published, to enable better performance for Chrome and Google application users.

SPDY protocol was created on top of TCP to enable something very different from the original idea of HTTP/1.1. First, instead of a connectionless paradigm, it was based on a long connection between the server and the client (in place of a series of HTTP keep-alive tricks). Secondly, rather than having to play with multiple domains to optimize the limited number of connections between the client and server as it allowed multiplexing, it sent multiple requests and received multiple responses using only one connection, and datastreams were possible at last. Binary replaced text as default encoding to minimize payloads, and better built-in support for encryption was also added.

So we have connections instead of connectionless and binary instead of text.

Based on SPDY, HTTP2 specification and implementations were created.

It is (almost) perfectly suited for modern web pages full of images, external scripts, style sheets and other resources. HTTP 2 greatly reduces the time needed to load a webpage or modern web application. It’s also much better for mobile applications, for similar reasons.

Is this the end of HTTP history, or at least its ten years of domination? Not this time.

→ gRPC – remote procedure calls’ choice for the 2020’s?

‘Almost’ is the spoiler word here. Most likely, HTTP2 had some limitations and Google is probably already using the next generation of technologies for their purposes (Chrome + Google services).

Yes! They did it again and called it QUIC. This doesn’t mean just Google, but the consortium consisting of all major players in IT, also including Apple, Microsoft, Mozilla, Facebook, Akamai, F5, and CloudFlare.

Why?

HTTP2 with its permanent connection works perfectly when we have a good, fast, and stable connection between the client and the server, so the benefits are clearly seen there. But what about a less reliable mobile oversaturated connection over 4G in the crowded areas or where the signal is weak? Well, HTTP2 does not work too well in those scenarios because it has to re-establish the TCP connection and loses all of its performance benefits.

Imagine having tens of requests multiplexed in a HTTP2 connection, suddenly the connection drops a pocket and . . . you lose everything. Everything has to be started from the beginning, again.

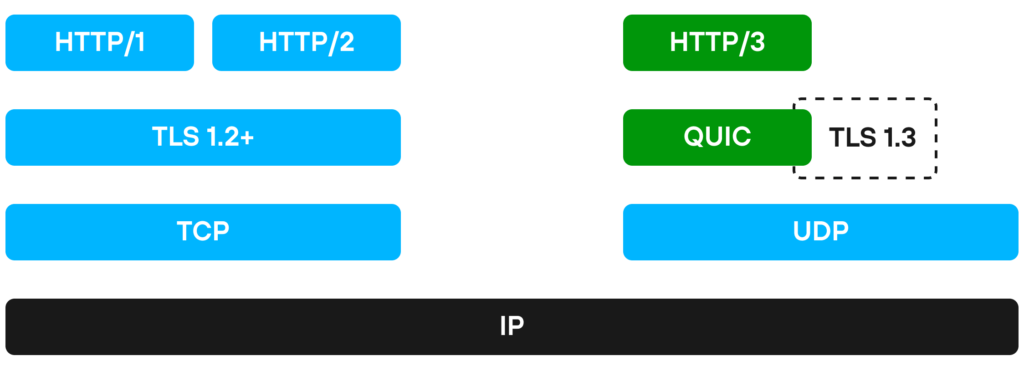

Another reason is TLS (successor of SSL). In the case of both HTTP 1.x and HTTP 2 it was an additional security layer on top of TCP which was not perfectly efficient.

How?

The protocol was designed from scratch and . . .it wasn’t even using TCP but UDP. UDP? UDP is faster and more lightweight and it does not have any acknowledgement segment. But using UDP does not guarantee anything, fortunately it’s not plain UDP.

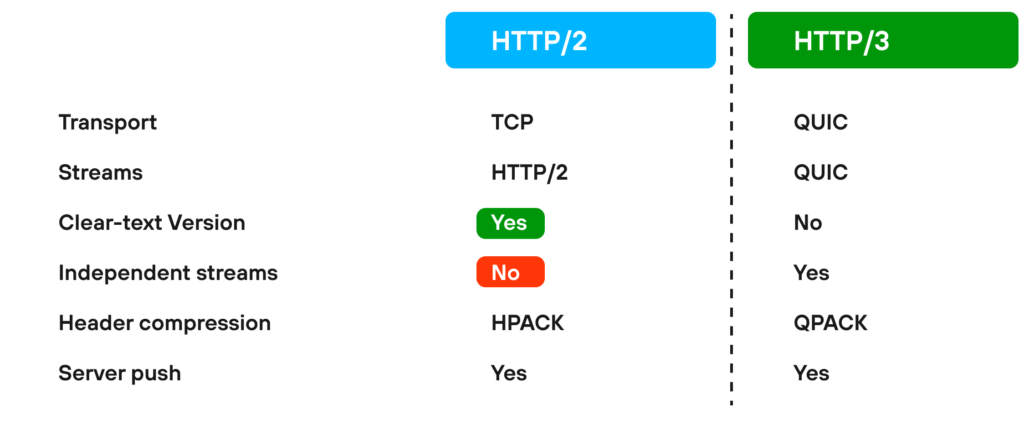

It’s a binary similar to HTTP 2, but it has its own flow control and reliability mechanisms which are expected to be better than in the aging TCP. The data streams in QUIC can fail independently, for instance when a user downloads two images, breaking the stream for one image won’t affect the second image. In the case of HTTP2 the entire set of streams would be lost.

It combines the reliability of TCP with the speed and low overhead of UDP, a combination of two worlds, by creating a lightweight and smart control layer on top of the UDP protocol.

For instance, to slow down sending requests when the network or server is unable to keep up with the clients demand, it uses advanced heuristics to let the user receive the data without going into a ‘timeout’ type of situation.

QUIC changed significantly from the original Google version to IETF QUIC.

Based on this newer IETF QUIC the new HTTP/3 specification was created, discussed and accepted. HTTP/3 is not QUIC, but is heavily based on it.

There are also voices suggesting QUIC will replace TCP for all other TCP based protocols, one by one.

The entire idea of a good protocol is to make it invisible to the users (I mean for all of us). So, when browsers and web servers fully support it, all users can benefit from it without even realizing it is there.

The same hope applies to the API and application developers. They should be allowed to just ‘enable’ it and the underlying support should do all the rest to make the apps work better.

→Generic API or Back-End for Front-End? You can have both.

There’s still verbs, headers, request and response bodies. The top application layer of the protocol is the same one we’ve all gotten used to. The important change is in the underlying transfer mechanisms. So it’s HTTP over QUIC, not over TCP. Feature comparison:

Feature comparison:

Google claims around 50% of the requests between Chrome browser and Google services (search, mail, docs) are already being performed by using a QUIC protocol. We can be optimistic that they will upgrade from QUIC to HTTP/3 easily. So in other words, Chrome and Google App users are already benefiting from HTTP/3 even though it may not technically be HTTP/3, but QUIC.

Preview versions of all the major browsers have HTTP/3 support baked in, soon to be enabled by default in official builds.

Web servers such as nginx have it planned in the following weeks (enabled by default).

It will take time for the entire internet to embrace the new protocol. The clients will be ready very soon but it will take time for back-end APIs to expose APIs using HTTP/3, content delivery networks to switch from HTTP/2 to HTTP/3, and there will be legacy apps still stuck in HTTP/1.1.

There will be configuration changes required, such as enabling UDP traffic which is very often blocked now. The new protocol is also very CPU intensive, requiring two or three times more CPU power to handle the same bandwidth. UDP stacks are not optimized in linux kernels, because of the lesser importance of the UDP stack so far (which is about to change now).

HTTP/3 wasn’t built to simply be better than HTTP/2 in the perfect network scenario. It is expected to work better when the network is unreliable.

How does it behave in perfect conditions? Like local 1 Gbps LAN with no packet loss?

The tests show the Time-To-First-Byte is 20%-30% lower than in HTTPS/2 (with TLS), so it proves the initial handshake is faster with QUIC than with TCP+TLS which was the expected result (although the boost was expected to be even bigger).

Real world tests with slower networks, different nodes and clients show HTTP/3 is slower on average a few percent than HTTP/2. This is usually explained by a lack of optimization both on the server and on the client’s side. When the protocol becomes more popular, significant implementation improvements are expected.

The client time (the time that client spends to encapsulate the data/extract the data) is up to seven times longer in HTTP/3 than in HTTP/2 or HTTP/1.1. CPU usage on the server and the client is 200%-300% larger.

So it’s not as rosy a picture as you’d expect given the promises of the protocol. All the sources repeat the same mantra, “it’s going to improve, and there will be better kernel support and hardware acceleration” (dedicated chipsets).

HTTP/3, as a major change to the protocol, is expected to take a long time for broader adoption, and an even longer time to become the dominant protocol. The major internet players, such as Google, Facebook, and CloudFlare, are the first to fully adopt and ship HTTP/3 services.

The others will have to wait for stable linux kernel support for the new protocol and changes in the infrastructure. It will all take time, but in a year or two the majority of us will be able to benefit from the improved user experience in both fast and unreliable networks.

We, at Avenga, believe that technology is an instrument to match market offerings to users’ needs. While closely watching, experimenting and excelling in innovation, we focus on pragmatic delivery of impactful results to our client’s digital initiatives.

* US and Canada, exceptions apply

Ready to innovate your business?

We are! Let’s kick-off our journey to success!